Evgenii Dulepinskii

This Station on Instagram

Colonialism as an inverse process

When it comes to German colonial history, one may think that it took place in Africa, China and the "exotic South Seas". These areas were colonized and some are still directly or indirectly under the influence of the West today. However, the reaction of the local population to contact with Western modernity had not been passive, but active – ranging from resistance to incorporation[1](appropriation), notes Kader Attia. "Everywhere where humans have been colonized, they have made artifacts from familiar old indigenous materials, but always with the conscious incorporation of strong symbols of power".[2]These symbols of power were adopted from Western modernity and represented, for example, portraits of European emperors and empresses, or images of weapons previously unknown to them.

Of course, colonialism mainly took place in overseas regions, note Ulrich van der Heyden and Joachim Zeller in the book "Kolonialismus hierzulande," but "the centuries-long 'colonial project' of Europe, in which the Germans – with and without their own colonial possessions – had their share, [is] today also understood as an inverse process"[3], which had "effects and repercussions of colonial rule on the former imperial powers".[4] hat.

Modernity and "Primitivism"

At the beginning of the 20th century, Western society experienced a shaking of the traditional worldview. Several artists felt this crisis and sought its solution in the confrontation with "folk traditions".[5]As a result, the phenomenon known as colonial modernity emerged. This term offers "a new approach to understanding the interrelationship between modernity and colonialism".[6] The term "primitive" in the art movement of primitivism is of course not value-neutral and has highly colonial connotations. In art history, however, primitivism was initially used to describe primarily European works that, like Paul Gauguin, were inspired by non-European modernism and thus questioned realism and fidelity to the image. Nevertheless, the term carries the problem that a society that considers itself to be more developed allows itself to be "inspired" by art forms that are considered regressive by its own society.

The sources of inspiration in non-European art consisted of a "large complex of non-classical or non-professional artistic expressions".[7]They represented a source of inspiration for modern artists. This is clearly visible in the early Bauhaus with its avant-garde school, which acted as a workshop of ideas in which new impulses were perceived and processed. Many Bauhaus students and teachers experimented with "primitive" art and non-European motifs. This work deals with those confrontations that are considered groundbreaking and revolutionary, but have a problematic legacy.

It is striking that both the Bauhäuslers themselves at the beginning of the 20th century and the modern authors who write about the early Bauhaus make little or hardly any mention of African influences on this art. And when they do make it a topic, they often lapse into problematic language. Moreover, it should be pointed out here that the influences were not attributed to African but to European artists, for example, of the Bauhaus, who succeeded in appropriating structures and elements from African arts.

Colors and Shapes

Wassily Kandinsky was one of the first artists to begin making paintings of exclusively abstract objects. He had studied ethnography in Moscow, among other things, and was considered "the intellectual originator and leading head of the folk-original orientation"[8] among Munich expressionists. Kandinsky said that art "seeks help from the primitive".[9]He turned to this help himself in painting. In doing so, he strove to break away from conventional studio painting and therefore faced the indignation and rejection of the general public and critics.

His own style, however, was not always of this nature. Still at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century he tended to a classical representation of reality in his paintings, but after his trip to Africa it is clear to see how Kandinsky's style was enriched with new experiences.

After his stay of several months in Tunisia in 1905, Kandinsky developed a theory about the psychological effect of pure color and formulated it in the book "On the Spiritual in Art". He wrote:

"The eye itself is charmed by beauty and other properties of color. The spectator feels a sense of satisfaction, pleasure, like a gastronome when he has a delicacy in his mouth. Or the eye is stimulated, like the palate by a spicy dish".[10].

On form, he said:

"The freer the abstract of the form lies, the purer and thereby more primitive it sounds. In a composition, therefore, where the physical is more or less superfluous, one can also more or less omit this physical and replace it with purely abstract forms or with physical forms translated entirely into the abstract".[11].

After the "Neue Künstlervereinigung München" rejected his abstract works, Kandinsky resigned from the association along with Franz Marc. Several artists followed them later. Thus, in 1911, a new group of artists was formed under the name of Der blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) which was about to become world famous. In fact, it was not an association and the only thing that united them were exhibitions held together, but in the framework of which no unified form of expression emerged. Kandinsky commented on the styles of The Blue Rider: "The greatest difference on the outside becomes the greatest equality on the inside".[12]And the inside was a longing for the strange, the perceived exotic and miraculous.

While still preparing for the first exhibitions, the two artists felt faced with the task of publishing the almanac called Der blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) . It should become the organ of all serious currents of the time[13], as the authors claimed. According to Franz Marc, the programmatic work included "the latest painterly movement in France, Germany and Russia" and showed "its fine connecting threads with the Gothic and the Primitives, with Africa and the great Orient, with the so expressive original folk art and children's art, especially with the modern musical movement in Europe and the new stage ideas"[14] of that time.

With this background, Wassily Kandinsky was appointed by the Master Council of the State Bauhaus in 1922. His appointment was part of the efforts of Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus, to expand the circle of avant-garde artists at the art school. Here Kandinsky further developed his non-figurative form of expression into geometric abstraction. Here, again, African art is associated with the childlike, problematically constructing a regressiveness that relates to familiar discourses about Africa as a continent in its infancy.

The other painter and future teacher at the Bauhaus, Paul Klee, only achieved a real understanding of color and painting during his trip to Africa in 1914. While in Tunisia, which was then under the protectorate of France, he created his vibrant watercolor paintings to reflect the saturated colors and lights of the landscape in North Africa. To him, this was a "colorful initial experience".[15]In his diary Klee wrote: "It enters me so deeply and mildly, I feel that and become so sure, without diligence. The color has me. I don't need to hunt for it. It has me forever, I know that. This is the meaning of the happy hour: I and the color are one. I am a painter"[16].

During his time of teaching at the Bauhaus in 1921 he painted the picture Der Töpfer (The Potter), which depicts a row of conventional vessels on the far right and a mask portrait of the potter on the far left. The motif of a mask is repeated in Klee's work in 1922, when he painted one of his most famous paintings, Senecio , a colorful abstract portrait. In the composition of the painting we can see influences from African mask and doll culture. In accordance with Kandinsky's form of expression, the main object – the old man's face – consists of primary individual parts: Square, Triangle and Circle.

Wood and Fabric

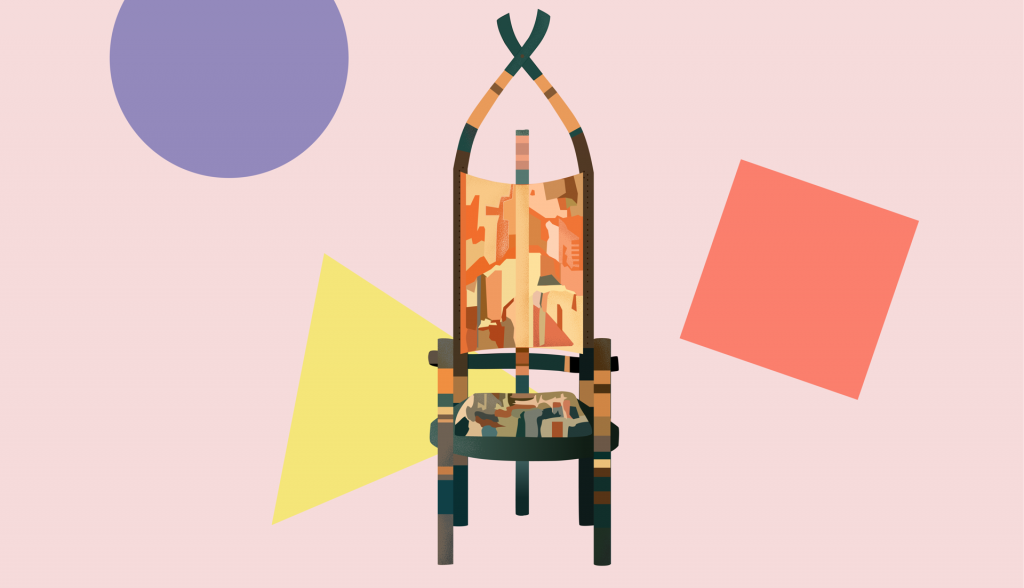

The "throne-like" chair made of painted oak and cherry wood is supported by five legs. The function of three rear legs is not only to ensure the stability of the work of art, but they rise and form a backrest with gaps. At their height, the two side struts of the backrest cross each other in a curved shape. They serve as a frame for the stretched warp threads with free shaping, from which an abstract colored pattern is created. The seat cushion is also made in the so-called Gobelin technique.

On the dark frame and posts are clearly visible traces of hand engraving. The painting of the wooden frame emphasizes the expressive colorfulness of the textile covering. Together they are supposed to be based on works of African art.

Where does this piece of furniture come from? And what purpose should it serve? At first glance, it may seem that the chair is one of those appropriated objects that were shipped en masse from the African continent to Europe in the age of colonial expansion. But its origin goes back to the carpentry workshop at the Bauhaus, where it was designed in 1921 by the Bauhäuslers Marcel Breuer, furniture designer and future head of the furniture workshop, and Gunta Stölzl, weaver and textile designer and future head of the weaving workshop. The named it"African chair".The designers did not give any hints about a possible use of the "throne", but what the very name of the work reveals is that they were inspired by the art heritage of Africa, which was articulated in a generalizing way without making a more precise differentiation. Of her working method Gunta Stölzl told the following: "I stretched the warp threads of coarse yarn directly on the chair seat and back through fine holes and stuffed gobelin-like forms into it"[17]. "The warp threads that remain visible, the clear machining marks on the wooden elements, as well as their painting"[18] show that the artists had dealt with "non-Western" motifs or projected certain expectations onto them. It would probably not have occurred to them to design a "European chair" named as such in the same homogenizing manner.

Other participants in the weaving course at the Bauhaus were also enthusiastic about African art conceived in this way. After the preliminary course, Anni Albers joined the workshop for weaving under the direction of Gunta Stölzl. While still in the preliminary course, Paul Klee had awakened in Anni Albers an interest in abstraction. "By looking at what he was doing with a line or a dot or a brushstroke" Anni Albers learned to find her way through her own materials and her own craft[19]. Like the Bauhaus master Klee, she was inspired by the non-European heritage. Because of her Jewish origins, Anni Albers and her husband had to flee to the United States as early as 1934, taking with them their fascination with indigenous First Nations cultures. From the United States, the couple made regular trips to Mexico and Peru, "fascinated by the artistic quality and "timelessness" of the "ancient craft".[20]In 1965 Anni Albers published the book "On weaving", which she dedicated to her "Great teachers, the weavers of ancient Peru".

Clay and Glass

In 1920, Walter Gropius set up the Bauhaus pottery in Dornburg. The craftsman training was led by the ceramist Max Krehan, who owned a tradition-bound pottery workshop at this location. Many of the prominent German potters of the 20th century apprenticed there. Many works produced in the ceramics workshop were influenced by African motifs and what was considered oriental. Edward Said referred to these methods as Orientalism and the artists who built an improved Western culture at the expense of the Orient as Orientalists[21].

Thus, a number of the vessels and jugs were made in the Bauhaus pottery by various artists, which can hardly be distinguished from the earthenware originating from the African continent by imitating their shapes and patterns. Max Krehan, for example, created the shape of a handle bottle from sand-colored shards, and Gerhard Marcks decorated it with a naive depiction of a team of oxen plowing. Marguerite Friedlaender also created a jug with a handle from sand-colored shards, on which an image of cows was depicted, probably also by Marcks.

The tile created by Gerhard Marcks with a portrait of Otto Lindig for a stove dates from 1921 and was "a symbol of the community between teachers and students"[22] of the Bauhaus pottery workshop. The whole portrait consists of curved lines. The clarity of the composition lines, like the painting "Senecio" by Paul Klee, refers to African mask and doll culture, or rather to the idea that the artists had of it.

Another mask, which is also noteworthy, although it comes from another workshop, is made mostly of glass, stands on a wooden plate and is decorated with feathers. The artist Margit Tery-Adler depicts a dragon's face with a glass triangle. The transparent mask with the peacock feather tiara is captured by an unknown photographer in front of a studio window. Looking at the work brings up memories of colonized peoples who took over symbols of power from Europeans but made their artifacts from familiar old native material.

Conclusion

At the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, long-running processes of globalization had already accelerated. Colonialism and foreign business, modern means of transportation and communication contributed to the spread of cultural art objects worldwide. Although art from Africa became very popular at that time because of its specificity, it was neglected in the international art scene. This is suggested by at least two facts that occur in this article. First, art from Africa has been generalized as "African art," although no uniformity exists that would define an African style. Second, its non-objectivity has been called "primitivism," while the art objects by Western artists inspired by the "primitivism" just mentioned have been called "abstract art." It is noteworthy, however, that in contrast to many art dealers who considered the African continent an easy acquisition and robbed its heritage en masse, Africa and its art were a real source of inspiration for several artists. They did manage to shape a positive, but also kitschy and exoticistic representation of art from Africa in the Western world. The image of the "noble savage," for example, is an stereotype overloaded with projections by Western artists such as Gaugin and others. Most importantly, the artists themselves have profited and made careers out of their appropriations, rather than introducing the general public to artists from Africa.

Bibliography

- Anz, Thomas; Stark, Michael (1982): Expressionismus: Manifeste und Dokumente zur deutschen Literatur 1910 – 1920, J. B. Metzler, Stuttgart.

- Bilang, Karla (1990): Bild und Gegenbild. Das Ursprüngliche in der Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts, W. Kohlhammer GmbH, Stuttgart.

- Bittner, Regina (2017); Artikel: Lernen von den anderen: Was das Bauhaus im Museum suchte

- Bunge, Matthias (1996): Zwischen Intuition und Ratio: Pole des Bildnerischen Denkens bei Kandinsky, Klee und Beuys, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart. https://cutt.ly/Or3NPGE

- Kader, Attia (2019):Kapitel: Koloniale Melancholie, in: bauhaus imaginista, Verlag Schneidiger und Spiess AG, Zürich.

- Kandinsky, Wassily (1912): Über das Geistige in der Kunst, insbesondere in der Malere,elektronische Version, München,

- Mercer, Kobena (2013): Kapitel: Kunstgeschichte nach der Globalisierung. Formationen der kolonialen Moderne, in:Das Bauhaus in Kalkutta. Eine Begegnung kosmopolitischer Avantgarden, Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern.

- Radewaldt, Ingrid (2018): Gunta Stölzl. Pionierin der Bauhausweberei, Weimarer Verlagsgesellschaft in der Verlagshaus Römerwer GmbH, Weimar.

- Said, Edward (2003); Orientalism, Penguine Books, London.

- Schiebler, Ralf (1985): Deutsche Kunstdogmatik, Herakles Verlag, Wuppertal.

- van der Helden, Ulrich; Zeller, Joachim (2017): Kolonialismus hierzulande: Eine Spurensuche in Deutschland, Sutton Verlag, Erfurt.

Endnotes

[1] Kader, Attia (2019): Kapitel: Koloniale Melancholie, in: bauhaus imaginista, Verlag Schneidiger und Spiess AG, Zürich. p.112

[2] ibid.

[3] Ulrich van der Heyden; Zeller, Joachim (2017): Kolonialismus hierzulande: Eine Spurensuche in Deutschland, Sutton Verlag, Erfurt. p.9

[4] ibid.

[5] Bilang, Karla (1990): Bild und Gegenbild. Das Ursprüngliche in der Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts, W. Kohlhammer GmbH, Stuttgart. p.8

[6] Mercer, Kobena (2013): Kapitel: Kunstgeschichte nach der Globalisierung. Formationen der kolonialen Moderne, in: Das Bauhaus in Kalkutta. Eine Begegnung kosmopolitischer Avantgarden, Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern. p. 156

[7] Bilang, Karla (1990): Bild und Gegenbild. Das Ursprüngliche in der Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts, W. Kohlhammer GmbH, Stuttgart. p.8

[8] ibid. p. 105

[9] Kandinsky, Wassily (1912): Über das Geistige in der Kunst, insbesondere in der Malere, elektronische Version, München, p.11

[10] Kandinsky, Wassily (1912): Über das Geistige in der Kunst, insbesondere in der Malere, elektronische Version, München. p.11

[11] ibid. p. 98

[12] Schiebler, Ralf (1985): Deutsche Kunstdogmatik, Herakles Verlag, Wuppertal. p.41

[13] Radio Broadcast “Die Kunststunde“ from 26.07.2012 http://www.andalusien-art.de/Kunst_Essay_Andalusien_Art/Expressionismus_IV__der_Blaue_/expressionismus_iv__der_blaue_.html [15.02.2020]

[14] Anz, Thomas; Stark, Michael (1982): Expressionismus: Manifeste und Dokumente zur deutschen Literatur 1910 – 1920, J. B. Metzler, Stuttgart. p.27

[15] Bunge, Matthias (1996): Zwischen Intuition und Ratio: Pole des Bildnerischen Denkens bei Kandinsky, Klee und Beuys, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart. p.224

[16] ibid. p. 224

[17] Radewaldt, Ingrid (2018): Gunta Stölzl. Pionierin der Bauhausweberei, Weimarer Verlagsgesellschaft in der Verlagshaus Römerwer GmbH, Weimar. p. 68

[18] "African chair". https://www.bauhaus100.de/das-bauhaus/werke/tischlerei/afrikanischer-stuhl/ [19.02.2020]

[19] Anni Albers https://www.bauhaus100.de/das-bauhaus/koepfe/meister-und-lehrende/anni-albers/ [19.02.2020]

[20] Bittner, Regina; Artikl: Lernen von den anderen: Was das Bauhaus im Museum suchte https://cutt.ly/Or3NPGE [20.02.2020]

[21] Said, Edward (2003); Orientalism, Penguine Books, London

[22] Ofenkachel mit Portrait Otto Lindigs https://www.bauhaus100.de/das-bauhaus/werke/keramik/ofenkachel-mit-portrait-otto-lindigs/ [21.02.2020]